Seems simple enough right? But in practice it can be challenging, especially in larger organizations with many stakeholders and multiple agendas, to not only choose ambitious yet attainable goals, but to track progress towards those goals, and measure their contribution to the overall success of the organization.

Choosing the right target

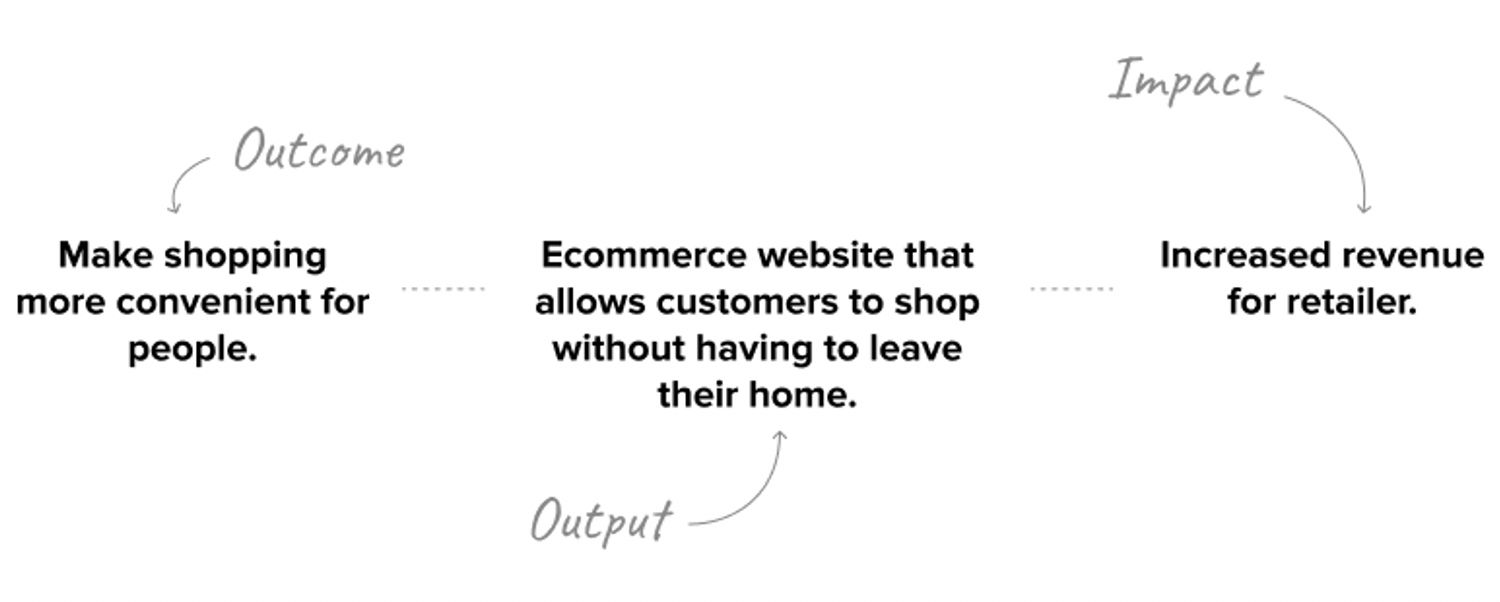

So first off, what do we mean when we say an ‘outcome’? In his book Outcomes Over Outputs, Josh Seiden defines an outcome as “a change in human behaviour that drives business results” (in this context ‘business’ refers to any organization, for-profit or otherwise). Often clients will come to us in order to execute on what they already think they need, say, a new website. And that’s great, we make amazing websites 😉. But a website is an example of an output. It’s a thing, a product, some tangible deliverable (yes, obviously not actually tangible), that we will produce. When we jump straight to the ‘thing' we’re making, we miss out on the opportunity to understand the broader reasons for why we’re making it, or whether it’s even the right thing to make in the first place! If we focus all our efforts solely on the output—the making of a website—we'll deliver beautiful designs, carefully crafted copy, and clean, semantic code... but not necessarily any actual customer or business value. Because the scope of success becomes whether we launched a website on time and within budget, not whether that website led to a desired effect. To borrow a phrase we use a lot, ‘it’s not just about building the thing right, it’s about building the right thing’. If one’s only intent is to build a website, $14 and a Wix account will get you there much faster and cheaper.

So how do we deliver ‘value’ over ’stuff’? Well, we start by asking questions. We may run a workshop with some sticky notes and sharpies and delicious pastries (or in COVID times, Miro and Zoom and burnt toast). We will likely ask the same questions multiple times in different ways or rephrase our clients' answers in our own words. I know, it’s annoying, but it helps us get a better overall understanding of the current situation, what problems may exist and for whom, and align on a desired future state. The purpose is to uncover what change in human behaviour will drive the business results we care about.

It’s important to set the right level of fidelity when determining what our objectives actually are. Whereas setting a goal like 'making a website’ is strategically narrow and may not create much in the way of value, goals like ‘making more money’ or ‘increasing market share’ are too broad and nebulous to try and solve outright. If making more money was a straight line from A to B, we’d already be doing it! We refer to these larger, high-level objectives as business impacts. Impacts are broader, aspirational goals and are the result of a complex mix of variables that can be difficult to attribute to a single output. Business is messy, humans are complicated, and we often don’t know for certain that doing ‘x’ will lead to ’y’. But we have ideas–hypotheses if you will, and by breaking large goals into smaller goals we make them more manageable and easier to track progress against.

The above is an oversimplified example that illustrates the power of outcomes. Notice the absence of a detailed solution in the outcome. There are lots of ways we may be able to make shopping more convenient for people. In fact, at this point the more ideas we come up with the better. We whittle down those ideas until we have a few that we think are worth trying out. And though it may seem obvious now, it wasn’t that long ago that it was still complicated and expensive to build an e-commerce website, and its impact on the business was far from certain given customer apprehension with entering credit card information, clunky checkout flows, etc. What we now take for granted was once a calculated risk, proven out by multiple ‘experiments.’

Let’s take a look at another example...

A not-for-profit public service is looking to redo their website. It’s about 5 years old and is feeling outdated. There’s a general dissatisfaction with how busy and cluttered it has gotten and some vague murmurings of 'bad UX', but other than that there is no clarity on what needs to be done or why, other than that it needs to be redesigned. Stakeholders will often focus on the visual aesthetic and what they don’t like or send through examples of sites they do like. But the question we need to start with is ‘what change in customer behaviour will drive the business results we seek’?

Since this is not a for-profit business, setting outcomes around increasing revenue doesn’t make sense. But all public services could likely benefit from the cost savings that come from being more efficient. So, the impact we are looking to influence over time is a reduction in cost. Now, there are lots of ways an organization can save money, but we are looking at how we might help achieve that through the lens of a better user experience, delivered via an updated website. Through talking with stakeholders, we learn that internal teams are spending considerable time addressing support tickets from users. Why? Is the application process confusing or cumbersome? Is certain content difficult to find, or perhaps missing altogether? All good questions, and we’d need to talk to users to know for sure, but it helps us formulate a hypothesis: An application process that is easier for users to understand and use we will free up internal resources currently tasked with resolving a high volume of support tickets. We don’t know whether this will result in any significant cost savings to the organization, but it is certainly reasonable to think that it might. What is clearer though is that having a simpler web app free of errors or ambiguity will almost certainly reduce the number of support tickets generated by confused users, because they will have an easier time getting through the process. And that’s our outcome. We can then come up with metrics for this outcome: how will we be able to tell whether this had the effect we thought it would? We can uncover other problem areas and develop outcomes for those as well. But at the end of the day we have a manageable target at which to aim. Not an arbitrary reduction in labour cost, and not a website of aesthetically pleasing randomness.

From Business Metrics to UX Metrics

According to design guru and maker of awesomeness Jared Spool, there are only 5 things execs care about:

- Increasing revenue

- Decreasing costs

- Increasing new business/marketshare

- Increasing revenue from existing customers

- Increasing shareholder value

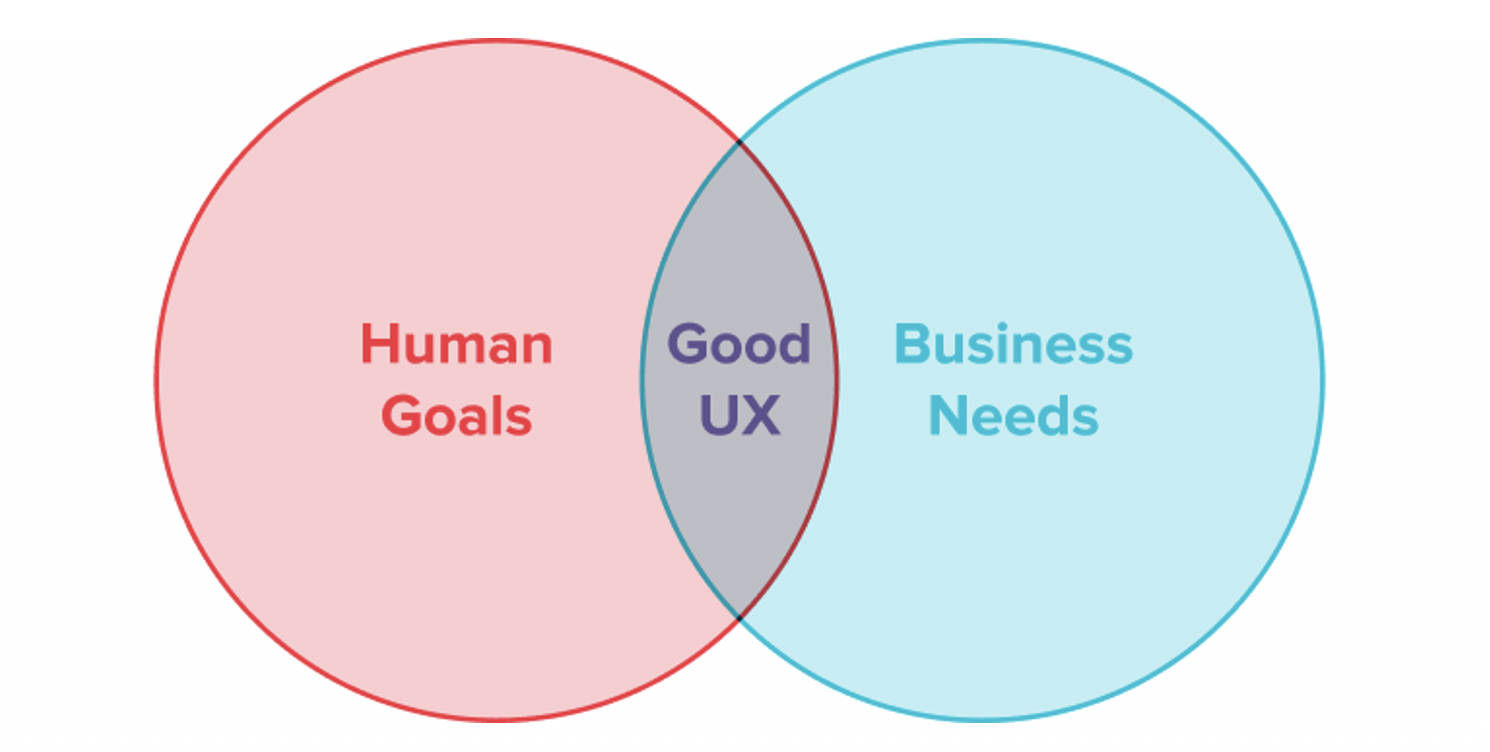

Whether or not there are outliers, it is likely that if we’re successful in achieving our outcomes, they will mainly contribute to one or more of these core business drivers. However, good organizations understand the need to also be thinking about the ‘user’ in user experience. Actions have to make financial sense for an organization to remain viable and sustainable, but there is little doubt left that companies who place high value and effort on delivering a superb user experience will win over companies that do not. To take the somewhat cynical view, it just makes good business sense. So, while all teams should be thinking about the business needs when determining their outcomes, it’s worth taking it one step further (or perhaps even starting here) to consider how an action will make someone’s life better. That is after all, what good design is about.

The magic of ‘so that...'

We know we should be considering how our planned initiatives will impact the actual users of our digital products or services. Aside from talking to and learning from users (which seems obvious at this point), here’s a cool little trick that we can use to reframe our business metrics as UX metrics: add ‘so that’ to the end of our outcome statement. Doing this quantifies a human-centred reason for our actions beyond just a business need. It tells us how it is intended to help someone. So, the above example would become If we design an application process that is easier for users to understand and use, we will free up internal resources currently tasked with resolving a high volume of support tickets, so that:

- they may focus their efforts on better servicing support edge cases

- they can get [payments, licences, documentation, etc.] out to customers more quickly

- they can enhance customer service delivery in other areas of the organization

Not to mention the decrease in frustration our applicants will experience when using the website!

Getting familiar with aligning our efforts around outcomes is extremely powerful. The more we can get in the habit of describing work in terms of actions that drive results, the more value we can hope to provide, instead of just more stuff. Regardless of whether we start with the business or with the user, a good UX strategy with properly defined outcomes will ultimately benefit both.